New Allman Brothers Band Book ‘Brothers and Sisters’ out Next Week – Read This Exclusive Excerpt That Gives a Fascinating Inside Look at the Group’s “Ramblin’ Man” Recording Session

The band’s history comes to vivid life in the much-anticipated follow-up to author Alan Paul’s ‘New York Times’ bestseller, ‘One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band’

When Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident on October 29, 1971, it seemed as if the Allman Brothers Band were history. In fact, their greatest days still lay ahead of them. Duane’s co-guitarist, Dickey Betts, stepped into the breach and took control. First he rallied the group to tour in support of 1972’s Eat a Peach, the follow-up to At Fillmore East, the 1971 double live album that brought the Allman Brothers the commercial and critical acclaim they so deserved. He then led them to create what would become their commercial breakthrough: the 1973 studio album Brothers and Sisters.

Supported by such stellar Betts compositions as “Jessica” and the chart-topping hit “Ramblin’ Man,” Brothers and Sisters went on to sell seven million copies and established the Allmans as one of the decade’s biggest groups. But the album’s wildly successful infusion of Betts’ country-rock also helped to pave the way for the success of other southern rock bands, like Lynyrd Skynyrd, who made their record debut that same year.

Without a doubt, the Allman Brothers dominated this era of American culture, from their massive shows with the Grateful Dead (their Summer Jam at Watkins Glen in July ’73 was attended by some 600,000 fans) to their support for Jimmy Carter that helped elect him to the presidency in 1976. Betts and keyboardist/guitarist Gregg Allman also enjoyed solo success when their respective 1974 albums – Highway Call and The Gregg Allman Tour – landed in the Top 20.

But the good times were marred by tragedy, from the death of bassist Berry Oakley shortly after the band began recording Brothers and Sisters, to the drug-fueled lifestyle that followed. The Allman Brothers Band dissolved in 1976, ending the first chapter in their long run.

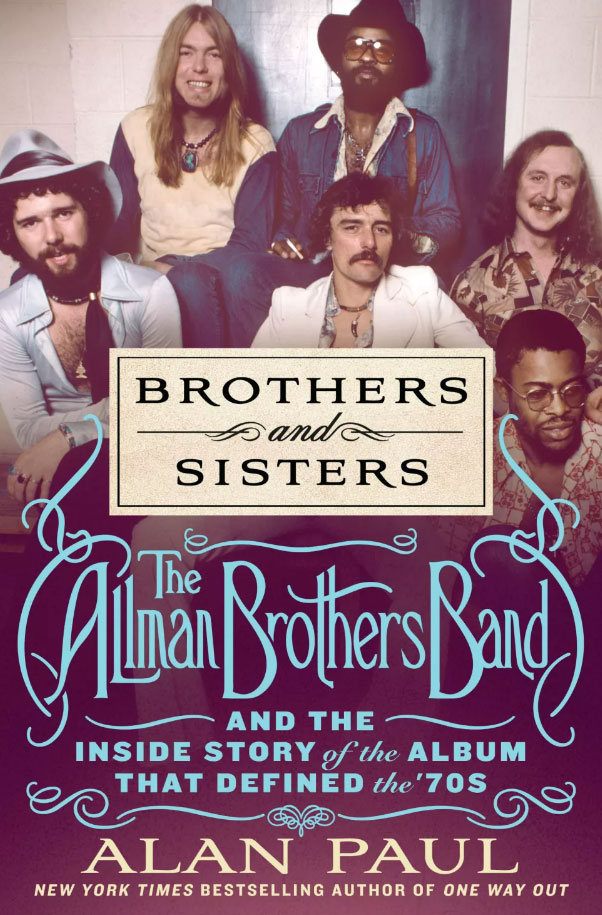

This era in the Allman Brothers Band’s history comes to vivid life in Alan Paul’s new book, Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the ’70s. Out this July 25 from St. Martin’s Press, the book is the much-anticipated follow-up to Alan’s New York Times bestseller, One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band, the definitive biography of the celebrated group.

In this exclusive excerpt from Brothers and Sisters, we present an inside look at the group’s recording session for “Ramblin’ Man.” The action picks up shortly after the group hires keyboardist Chuck Leavell, fresh from his sessions for Gregg’s solo debut, Laid Back, and brings in guitarist Les Dudek to assist Betts.

From Brothers and Sisters by Alan Paul. Copyright © 2023 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Chuck Leavell’s musical imprint is unmistakable on the first two tracks the band recorded, Gregg’s “Wasted Words” and Betts’ “Ramblin’ Man.” He added a bounce that elevated “Wasted Words,” undergirding Betts’ slide guitar, which was less fluid and expansive than Duane’s and more attuned to playing a defined melodic part. Gregg had recorded a demo of “Wasted Words” in Los Angeles on August 9, with Johnny Winter on guitar and Buddy Miles on drums. Betts’ slide line sounds like it was inspired by what Winter had played on the demo.

The lyrics of the song are a brutal kiss-off to Gregg’s first wife, Shelly Winters (not the actress), including his own admission of failure:

Well, I ain’t no saint and you sure as hell ain’t no savior…. Don’t ask me to be mister clean, baby, I don’t know how.

This was followed by a brutal line:

Your wasted words, so absurd / Are you really Satan, yes or no?

The song kicked off the sessions with swagger, which continued in a totally different vein with “Ramblin’ Man.” The two songs, one an Allman rock blues, the other a Betts country rocker, are entirely different but sonically linked by Leavell’s honky-tonk bravado. His sound is singular, even as you hear elements of the musicians the pianist cites as his prime inspirations: Ray Charles, Nicky Hopkins, Dr. John, Leon Russell and Elton John. He wasn’t particularly influenced by country music, but his instincts naturally took him to some traditional playing on “Ramblin’ Man,” bringing to the song a genuine country swing.

“I just followed my ear and played what seemed appropriate,” Leavell said.

“Ramblin’ Man” was different from anything the band had ever recorded before. The only thing close was “Blue Sky,” another major-key song with a country bounce. But “Blue Sky” wasn’t all that country, as Betts would note. “It was more of that country/rock thing that was popular at that time. It could have been done by Poco or the Dead.”

“Ramblin’ Man” was much closer to being an actual country tune. Betts said the Hank Williams song of the same name inspired his initial idea, with Dickey’s lyrics adapting Williams’ “when the Lord made me, He made a ramblin’ man.” Betts originally thought he’d offer it to a country artist but was surprised to learn that he was the only guy in the band who thought it was too country for the Allman Brothers Band to record. “I was going to show it to Hank Williams Jr. and ask if he wanted to cut it,” he said.

Gregg had no issues adding the song and broadening the band’s range. “Hell, that song cooked,” he said. He was glad the band recorded it and that Dickey didn’t save it for a solo album, as he had suggested he might do.

Decades later, after years of conflict with Betts, Trucks would scoff at the song, alluding to Dickey’s initial inclination to give it to a country artist, by saying the band thought they were “recording it as a demo for Merle Haggard or someone.” But all indications are that the song was always intended to be an Allman Brothers release and that the group almost immediately knew that they had hit on something beautifully different.

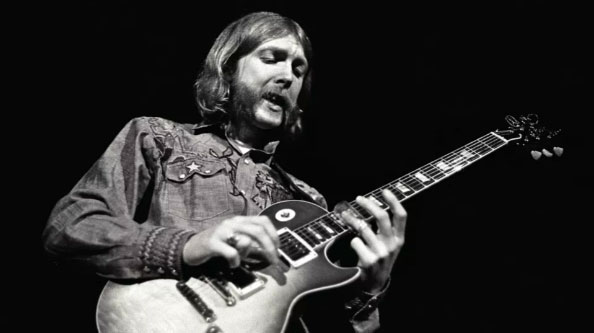

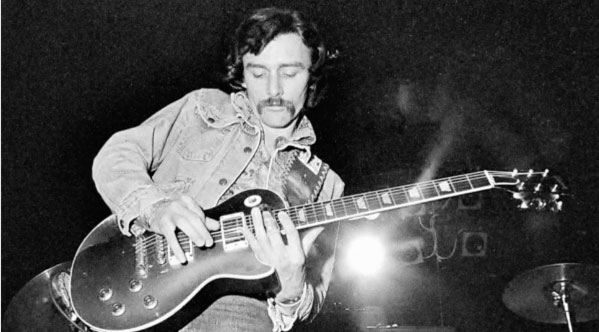

Duane Allman, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, May 1, 1971. Duane was the undisputed leader of the Allman Brothers Band. No one knew how the band could continue after his death on October 29, 1971, but they were determined to do so.

Duane Allman, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, May 1, 1971. Duane was the undisputed leader of the Allman Brothers Band. No one knew how the band could continue after his death on October 29, 1971, but they were determined to do so.

“I can’t remember any discussion whatsoever about ‘Ramblin’ Man’ being too country to include,” said Leavell. “I certainly didn’t feel that way. I thought it was a marker of how great of a band it was that you could do a song like ‘Melissa’ followed by ‘Liz Reed’ followed by ‘One Way Out’ – and now Dickey was pushing that out to country rock.”

As much of a departure as it was, “Ramblin’ Man” was not a new song. Betts had been working on it for a few years and had played an embryonic version for Duane. He can be heard working through the song on The Gatlinburg Tapes, a bootleg of the band jamming in April 1971 in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, during Eat a Peach songwriting sessions. At that stage, the lyrics refer to a “ramblin’ country man,” but the chords, structure and concept are all in place. He finished writing the song about a year later in the kitchen of the Big House, the Allman Brothers’ communal home at 2321 Vineville Avenue (which now houses the Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House). He had written “Blue Sky” in the living room.

Betts said that he carried the germ of the idea around in his head for several years. Before the Allman Brothers Band’s formation, whenever he didn’t have a place to sleep, he’d crash at the Sarasota apartment of his friend Kenny Hartwick, whom he described as “a friendly, hayseed cowboy kind of guy who built fences and liked to answer his own questions before you had a chance.”

Betts was surprised to learn that he was the only guy in the band who thought ‘Ramblin’ Man’ was too country for the Allman Brothers Band to record

“One day,” Betts told writer Marc Myers, “he asked me how I was doing with my music and said, ‘I bet you’re just tryin’ to make a livin’ and doin’ the best you can.’ I liked how that sounded and carried the line around in my head for about three years. Except for Kenny’s line, the rest of the lyrics were autobiographical. When I was a kid, my dad was in construction and used to move the family back and forth between central Florida’s east and west coasts. I’d go to one school for a year and another the next. I had two sets of friends and spent a lot of time in the back of a Greyhound bus. Ramblin’ was in my blood.”

On the final version, Les Dudek, who had been jamming with the group and thought he might be hired as Duane’s replacement, plays sterling guitar harmonies with Betts, making a huge contribution to the song’s success. The two men had worked out all the parts together, but then Betts decided to play them all himself, cutting multiple tracks. Dudek was in the control room watching as Betts repeatedly came in and asked his opinion about various takes, before finally just saying, “Why don’t you just come out and play?” Dudek said they played their harmonies live, with Oakley “staring a hole” through him. The sight of another guitarist playing with Betts seemed to hit Oakley hard. “That was very intense and heavy,” Dudek said.

Brothers and Sisters producer Johnny Sandlin agreed that the entire band knew they had something special the moment Dudek and Betts finished their guitar parts. “We all knew it was really good,” he said. “The guitar playing is just amazing.”

As Trucks said, “Les added a lot to ‘Ramblin’ Man.’ He was a good, slick player and he and Dickey worked well together.”

In addition to its obvious country influences, “Ramblin’ Man” also shows Betts’ love of jazz big bands. For the coda, he wanted an orchestral approach with a huge sound. The song’s instrumental section had four guitars playing two different harmonies an octave apart and Betts’s final overdub, which was a slide guitar line. “I added that long instrumental ending in the studio to try and make it sound more like an Allman Brothers song,” said Betts.

Knowing that the song needed a strong intro to “grab the listener,” Betts turned toward the string band music he played with his family as a boy in Florida. He wrote a fiddle-style major pentatonic guitar line, which he then worked out as a call and response with Leavell. The pianist’s “Ramblin’ Man” contributions and his bouncy, swinging work that elevated the blues structure of “Wasted Words” illustrate the brilliant decision to add Leavell instead of replacing Duane with another guitarist. His role at the heart of the music would only grow over the rest of the album sessions.

“It was just a happy accident – certainly nothing that was by design,” said Leavell. “Nobody said, ‘Let’s get a piano guy!’ It happened by osmosis, more or less out of the blue from an unexpected direction, which is maybe why it wound up working as it did.”

Even as the recording sessions were going well, the band remained concerned about Oakley and his drinking. Sandlin said that many of the initial sessions had to wrap up early because Berry became too inebriated to continue. The producer said that he played bass as the band learned “Ramblin’ Man” because Oakley hadn’t shown up and that the band even questioned whether Oakley “would be able to be on the album at all.”

They were all aware without openly discussing it that the first anniversary of Duane’s death was approaching. Heaviness hung in the air, particularly around Oakley. Still, his playing on “Wasted Words” and “Ramblin’ Man” was excellent, and there was hope that he was coming out of the year-long depression. Oakley was particularly buoyed by Leavell’s arrival. “He started playing his ass off again after Chuck joined,” said Jaimoe. “It was like he saw the light and the old Berry was back.”

An enthused Oakley went out of his way to make the new member feel at home. “Berry and Jaimoe were the first ones to really welcome me into the band,” said Leavell. “Berry would put his arm around me, check on me, make sure I felt comfortable. He was very keyed into the dynamics of being the new guy and smoothing over that transition. He was also just the coolest guy.”

Harmonica player and frequent ABB musician Thom Doucette was at the first rehearsal the band had after Duane’s death. There to support his friends and maybe to be a part of the new band, he sensed heavy tension between Gregg and Dickey over who was in charge the moment he walked into the room. It was a feeling that Oakley shared, Doucette said.

“Berry and I looked at each other and understood what the other was thinking,” said Doucette. “What was is now over. It’s gone. It was just too weird. With Duane around, the Dickey/Gregg rivalry was never an issue, but without him, it was inevitable.”

With two songs in the can, the group played live for the first time after a nearly two-month hiatus on November 2, flying to New York for a short set at Hofstra University, as part of Don Kirshner’s In Concert TV show, which also featured Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chuck Berry and Poco. They debuted not only “Ramblin’ Man” but also their new lineup, back to six pieces and featuring Leavell. The pianist was thrilled to finally be onstage as a member of the Allman Brothers Band and was particularly keyed into Oakley’s distinctive playing.

“Berry was the most unique bass player I had ever played with,” said Leavell. “Rather than holding down the bottom end, he was very adventurous, constantly listening to the other instruments and popping out with great melodies. He was there to support anyone’s improvisation. I could feel Berry following me when I started a melody and it was just fantastic. He also had the most powerful rig and the coolest bass sound; you could feel it inside.”

While the characteristics of Oakley’s playing were apparent in the studio, Leavell said that they were especially evident onstage, where he drove the band. Leavell would only perform in concert with Oakley that one time. Just nine days later, on November 11, 1972 – one year and 13 days after Duane’s crash – Oakley, too, was killed in a motorcycle accident when he sideswiped a city bus, less than a quarter mile away from Duane’s crash site. Like Duane, Oakley was just 24 years old when he died.

Despite everyone’s acute knowledge of and concerns over Berry’s struggles, his death jolted the band. As they pondered their next moves, they immediately canceled two shows with the Grateful Dead, which would have represented their first official billing together since February 1970.

“We had finally gotten some good positive energy going again,” said Trucks. “The dynamic had turned with Chuck. Dickey was writing and singing his ass off. Everything felt like it was moving in the right direction for the first time since Duane’s death and then, bam, we were right back in it again.”

The band once again stood at a seemingly unthinkable crossroads. Not only had they lost two of the original six band members in one year, but they were essentially missing their corporate board. Duane and Berry were the group’s undisputed leaders, a general and his colonel, the two everyone else looked to for direction. “Duane had the vision and Berry got it done,” said Doucette. “They were so close.”

“Duane was very outspoken and Berry was a lot easier to deal with,” Jaimoe said. “You couldn’t talk Duane out of anything once he made his mind up. He was just so intense. Berry was more the voice of reason, a bit more diplomatic. In fact, Berry Oakley was the brains behind the Allman Brothers Band. He knew enough about how to do business, and he knew how to deal with people. Duane didn’t have Berry’s patience.”

Oakley’s loss left everyone in and around the band reeling. Gregg was in New York, on his way to Jamaica with his new girlfriend, Janice Blair, when he got word of Oakley’s death from Carolyn Brown, Walden’s secretary. “She called me and said, ‘Honey, if I was you, I’d go right on to Jamaica. You don’t need this, not again,’” Gregg recalled. He did not attend Oakley’s funeral, held at Macon’s St. Joseph Catholic Church on November 15. The remaining band played a desultory set of music, with Joe Dan Petty on bass.

“Berry’s death fucked me up the way Duane’s death did to him,” said Jaimoe. “Berry was my man. I got high on smack just to go to his funeral. Later that night, I nodded out in my car.”

Sleeping at a red light in downtown Macon, Jaimoe was rescued by a friend who happened to see him, ran to the car, and drove Jaimoe home to the Big House. It was a reflection of how deeply impacted the entire group was by this second tragic death.

“It was just like when Duane died,” said Sandlin. “Suddenly you’re just going through the motions of daily life. I really didn’t know how much more any of us could deal with. At that time, at our age, we didn’t know how to grieve properly. Most of us had not lost many people yet.”

“It was so hard to get into anything after that second loss,” Gregg said. “I even caught myself thinking that it’s narrowing down, that maybe I’m next.”

Order your copy of Alan Paul’s Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the ’70s here.